On September 12, 1962, at Rice University, John F. Kennedy gave an historic speech that would pave the way for perhaps the most dynamic moment in American history. The speech, titled “Address at Rice University on the Nation's Space Effort,” arrived at a time when the United States was losing the race for space to the Soviet Union, badly. Much can be written about this speech (indeed, much has been written about this in the succeeding 62 years) but most notably, Kennedy states that “We choose to go to the moon in this decade.”

Knowing that the Soviet Union has beaten the United States to nearly every important milestone in spaceflight, and that the next big milestone is landing a human on the Moon, Kennedy sets this goal (admittedly the most important milestone for spaceflight at the time) for the American space program to occur by the end of the decade. Kennedy says the word “decade” six times in his speech, to instill a sense of urgency. And while Kennedy himself did not live to see it, on July 21, 1969 (163 days before the end of the decade) Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to step foot on another celestial body.

One decade after that famous speech, the final Apollo mission left the Moon, and humans have not been past low Earth orbit since. As I write this, it seems likely that SpaceX’s Polaris Dawn mission will launch next week, and travel further into space than any human has since that final Apollo mission 52 years ago.

Yet the road to get here has been paved with massive delays and major cost overruns in nearly every aerospace project, company, and nation. While there are exceptions, the culture of space exploration is one of slowness and costliness. People living in the 1970s might be shocked to learn that, fifty years later, not only are humans not living in space settlements on the Moon and Mars, but humans haven’t even left low Earth orbit since 1972. The grand visions for the future of humanity in space that were being dreamt up while humans walked around on the Moon seem no closer today than they did at the end of the 1960s.

Space Delays

The progression into humans becoming a multiplanetary species is slow, and aerospace projects working on different aspects of this challenge almost never meet their initial target launch date. Cost overruns and massive delays plaguing the space industry are the rule, not the exception, but there are many possible explanations for why this phenomenon occurs. As with other industries, oftentimes an incumbent company will become complacent and fail to deliver against a lean, scrappy start-up- the modern day David vs Goliath story.

Boeing’s Starliner

The perfect example of this is Boeing’s Starliner program. In 2010, Boeing bid on the NASA Commercial Crew Program competition for post-Shuttle era missions to the International Space Station. With a decent production schedule, Boeing officials believed that Starliner could be operational by 2015. In September 2014, Boeing was awarded a contract (along with SpaceX), and intended to have its crewed test flight occur in 2017. This ended up slipping to 2019 (and became uncrewed), and was considered a partial failure. Due to this partial failure, NASA wanted another test flight; this was to occur in 2021, but an issue with the valves caused Boeing to halt the test and run tests; nine months later, Boeing successfully launched to the International Space Station.

After a few more issues that delayed the first crewed flight to 2024, in June Starliner launched to the International Space Station; on its way there, the capsule experienced thruster malfunctions, and while the capsule docked at the station for its eight day mission, Boeing and NASA officials delayed the return until tests could be run on Starliner, ensuring it could safely return. This is a timely example because, as of August 24, 2024, the decision has been made that the astronauts who went up to the International Space Station on Starliner will not return on Starliner, but instead will return in 2025 on a SpaceX vehicle, turning Boeing’s eight day mission into a likely eight month mission.

Artemis

The delays and cost overruns do not just plague the commercial space industry, however. The Artemis program, directed by NASA, intends to return humans to the Moon for the first time since 1972, and then permanently, with a planned lunar base. Artemis is to use the Space Launch System (run by government contractors and mandated by Congress). The first launch of the Orion spacecraft for the Space Launch System was intended for 2016; it actually launched in 2022.

The Artemis missions themselves were planned to launch much earlier as well. Artemis III, the mission that will actually see humans walking on the Moon for the first time since 1972, was originally scheduled for 2024; now, the program intends Artemis II to be on the Moon in 2026, but at the rate things are going with development and cost overruns, it will be a miracle if Americans make it back to the Moon by the end of the decade. The Artemis missions seem more likely to resemble the troubled development of the James Webb Space Telescope, which was supposed to launch in 2007 with a budget of one billion dollars, and instead ended up launching in 2021 with a final program cost of ten billion dollars.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

SpaceX

There are a few shining lights in the space industry, and the future belongs to them. Space technology start-ups are seeing general success despite years of hostile territory against billion dollar incumbent companies. Infrastructure is being built out by SpaceX, which offers a competing vision for the future of space development that is focused on speediness and purpose. SpaceX’s bold vision to “to build the technologies necessary to make life multiplanetary” isn’t just inspiring- it attracts a certain type of person to work on solutions to the problems in the world, and also has a ripple effect in the surrounding geographical area. SpaceX missions are rarely delayed, and when they are, they tend to be short delays, not the decade-long delays expected in the space industry. Under the same NASA contract as Boeing’s Starliner program, SpaceX has launched eight crewed missions to the International Space Station, with a ninth planned for next month. SpaceX’s rocket launch cadence is unbelievable, and one needs only compare SpaceX’s launch history to every other rocket provider combined to see there is something magic about SpaceX.

China

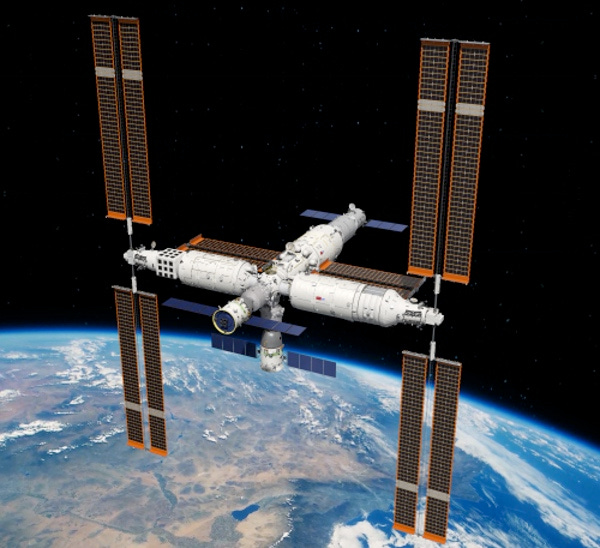

SpaceX may be the leader of space development and innovation, but they aren’t the only example of successful space development. China has grand ambitions in space, and seems to be overtaking new industries, from their satellite program aimed at ensuring dominance of the 6G landscape, to their space station, which is smaller than the International Space station but benefits greatly from its advanced technology. The International Space Station was launched into orbit in 1998, with additional modules being added sporadically over the years. Tiangong, the Chinese Space Station, was launched into orbit in 2021, and has seen constant additions in modules, with the next scheduled for 2026.

China is also serious about landing on the Moon before the end of the decade, which seems likely to actually happen. Plans are also in motion for China to lead the International Lunar Research Station, a lunar research base in which China has been assembling a coalition of nations to partner with, one that is in direct competition with the United States-led Artemis Accords. China has shown through their space program that it is possible to achieve milestones in a speedy manner, and if the United States refuses to get serious about speeding up their space ambitions, China will far outpace and beat the United States. Luckily, the United States can win if they embrace SpaceX and the new era of builders.

Thank you to Rob Tracinski, Emma McAleavy, and Mary Hui for feedback and comments on earlier drafts!

"Cost overruns and massive delays plaguing the space industry are the rule, not the exception"

Do you know if space is anomalous in this regard, or is it just that many space endeavors are megaprojects and that's the natural tendency of megaprojects (see, for example, the book Megaprojects and Risk). To what degree is this what we expect from 1. megaprojects usually going over budget and 2. space is extra hard and one mistake could be disastrous or incredibly costly (e.g. putting a contact lens on a telescope is pretty hard once it's in LEO)?

If it's roughly in line with what's to be expected, how confident should we be that the new era of builders can reach and maintain this better way? Is this likely or still relatively unproven?